I have kept journals for many decades. Even before my

creative writing professors encouraged me to keep them, I kept writer’s journals

after reading that writers I respected, such as Virginia Woolf and Madeleine L’Engle,

had kept writer’s journals. I have stacks and stacks of them, and periodically

I wade through years of them, reading and mining for ideas and memories

.

You will notice I did not say I’ve kept diaries. A diary is

an account of your day-to-day activities. A writer’s journal is the artist’s

sketchbook of a writer. It holds the raw material, the thinking on paper, that

goes into learning how to write better and into creating minor and major

projects.

A writer’s journal may have accounts of daily activities in

it, along with discussions of current events, descriptions of the striking

woman seen at the coffee shop, the idea for a new novel, the first few

paragraphs of a short story, lines or whole stanzas of a poem, descriptions of

the sound water makes dripping from trees into a fountain at the park, pages of

location or historical research, a scary near-miss turned by what-if into the

germ of a story or novel, lists of words I love, scenes recaptured from my

childhood or other past moments, and much, much more. Writing exercises. Lists

of possible titles. The initial sketches of characters. Accounts of dreams. Rants

and complaints and a good bit of whining, as well.

A writer’s journal may have accounts of daily activities in

it, along with discussions of current events, descriptions of the striking

woman seen at the coffee shop, the idea for a new novel, the first few

paragraphs of a short story, lines or whole stanzas of a poem, descriptions of

the sound water makes dripping from trees into a fountain at the park, pages of

location or historical research, a scary near-miss turned by what-if into the

germ of a story or novel, lists of words I love, scenes recaptured from my

childhood or other past moments, and much, much more. Writing exercises. Lists

of possible titles. The initial sketches of characters. Accounts of dreams. Rants

and complaints and a good bit of whining, as well.

Now, I also keep computer journals as I write each novel. This

is where I go deeper into character, work out plotting difficulties, set myself

goals for the next chapter or section of the book, and keep track of things

that impinge on the writing of the book. Older versions of this are what I turn

to when I need to find out how long I think it will take me to complete some

phase of the new book. Also, it’s where I look for encouragement when going

through tough times on a book. I almost always find I’ve made it through

something similar before. I keep my journals in bound books between novels and

in addition to the novel journals kept on the computer.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve found ideas or

characters or settings for stories, poems, and books while going back through

these journals—or found ideas that connect with other ideas I have to complete

the concept for a novel or poem. Also, as I look through them, I can see on the

page how my writing has improved over the years. I consider these journals

necessities for my continuing growth as a writer. Just as a musician continues

practicing the scales and more ambitious exercises daily, just as a painter

continues sketching constantly, I keep opening my journal and writing down a

description or an idea or a question I’m wrestling with or a character I’m

exploring. Madeleine L’Engle called her journal work her “five-finger exercises.”

I often tell young students to keep journals, even if they

don’t want to become writers. I believe it will help them navigate the fraught

waters of adolescence. I know it helped me come to terms with a damaging,

abusive childhood and write my way out of the anger, pain, fear, and shame it

engendered in me. I’ve used journaling as an effective therapeutic technique

with incarcerated youth, and I believe it’s something anyone can do to help

them work their way through emotional pain and problems.

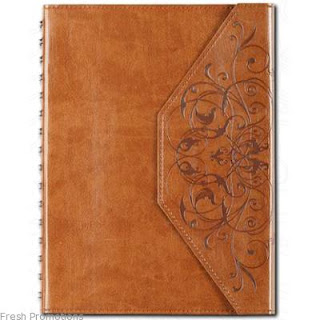

I have plain spiral notebooks, composition books, three-ring

binders, and an assortment of bound books of many sizes and appearances. I have

heard some people say they could never write in a really beautiful bound book

because it would intimidate them, but I write even in the gorgeous handmade

ones friends and family give me as luscious gifts. The act of writing is what keeps

me from becoming too intimidated to write.

If you’re a writer, do you keep journals? In notebooks or on

the computer or both? And if you’re not a writer, have you used a journal before

to work through thorny issues?